- Home

- M. L. Buchman

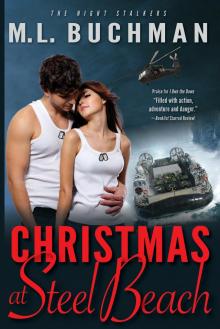

Christmas at Steel Beach

Christmas at Steel Beach Read online

The Night Stalkers

Christmas

at Steel Beach

by

M. L. Buchman

Dedication

To the USS Peleliu and those who built and served on her.

Many thanks for your thirty-seven years of service.

Note:

The USS Peleliu was launched in 1978 and is due to retire in 2015. The ship and the LCAC’s are as accurate to real-life as I could make them. To those who served on her and know better, my apologies.

Chapter 1

U.S. Navy Chief Steward Gail Miller held on for dear life as the small boat raced across the warm seas off West Africa.

The six Marines driving the high-speed small unit riverine boat appeared to think that scaring the daylights out of her was a good sport. It was like a Zodiac rubber dinghy’s big brother. It was a dozen meters long with large machine guns mounted fore and aft. The massive twin diesels sent it jumping off every wave, even though the rollers in the Gulf of Guinea were less than a meter high today.

Gail wondered if they were making the ride extra rough just for her or were they always like this; she suspected the latter. Still she wanted to shout at them like Bones from Star Trek: I’m a chef, not a soldier, dammit. But being a good girl from South Carolina, she instead kept her mouth shut and stared at her fast-approaching new billet.

The USS Peleliu was an LHA, a Landing Helicopter Assault ship. She could deliver an entire Marine Expeditionary Unit with her helicopters and amphibious craft. Twenty-five hundred Navy and Marines personnel aboard and it would be her job to feed them. All the nerves she’d been feeling for the last five days about her new posting had finally subsided, buried beneath the tidal wave of wondering if she was going to survive to even reach the Peleliu.

At first, the ship started out as black blot on the ocean, silhouetted by the setting sun that was turning the sky from a golden orange over to more of a dark rose color.

Then the ship got bigger.

And bigger.

In a dozen years in the Navy she’d been aboard an aircraft carrier only once, and it lay twenty minutes behind her. She’d been there less than a half hour from when the E-2 Hawkeye had trapped on the deck. They’d shipped her to the Peleliu so fast she wanted to check herself and see if she was radioactive.

It didn’t matter though; she was almost there. From down in the little riverine speed boat, her new ship looked huge. The second largest ships in the whole Navy, after the aircraft carriers, were the helicopter carriers.

Gail knew that the Peleliu was the last of her class, all of her sister ships already replaced by newer and better vessels, but even six months or a year aboard before her decommissioning would be a fantastic opportunity for a Chief Steward. Maybe that’s why they’d assigned Gail to this ship, someone to fill in before the decommissioning.

Fine with her.

She was still unsure how she’d actually landed the assignment. She’d spent a half-dozen years working on the Perry Class frigates as a CS, a culinary specialist. Her first Chief Steward billet had been at SUBASE Bangor in Washington state feeding submariners while ashore until she thought she’d go mad. She missed the ship’s galleys and the life aboard.

Then she’d applied for a transfer, never in her life expecting to land Chief Steward on an LHA. After the aircraft carriers, they were the premier of Navy messes. Chefs vied for years to get these slots and she’d somehow walked into this one.

No, girl! You’ve cooked Navy food like a demon for over a decade to earn this posting. Her brain’s strong insistence that she’d earned this did little to convince her.

And she hadn’t walked into this, she’d flown. It had taken three days: Seattle, New York, London, Madrid, and Dakar, each with at least six hours on the ground, but never enough to get a room and sleep. And then an eyeblink on the aircraft carrier.

It didn’t matter. It was hers now for whatever reason and she couldn’t wait.

The LHA really did look like an aircraft carrier. She knew it was shorter and narrower, but from down here on the waves, it loomed and towered. One heck of an impressive place to land, girl. She could feel the “new posting” nerves fighting back against the “near death” nerves of her method of transit over the waves.

The flattop upper deck didn’t overhang as much as an aircraft carrier, but that was the only obvious difference. Like a carrier, the Flight Deck was ruled over by a multi-story communications tower superstructure and its gaggle of antennas above.

On the deck she could see at least a half-dozen helicopters and people working on them, probably putting them away for the end of the day. It seemed odd to Gail that they were operating so far from the carrier group. It had taken an hour even at the riverine’s high speed to reach the Peleliu and she appeared to be out here alone; not another ship in sight.

In the fading sunset, the ship’s lights were showing more and more as long rows of bright pinpricks. The flattop was at least five stories above the water.

The riverine boat circled past the bow and rocketed toward the stern. Gail had departed the aircraft carrier down a ladder on the outside of the hull amidships. But here they approached the stern.

That was the big difference with the LHAs; they had a massive Well Deck right inside the rear of the ship. She’d seen pictures, but when her orders came, they’d been for “Immediate departure.” No time to read up on the Peleliu. So, she’d learn on the job.

A massive stern ramp was being lowered down even as they circled the boat. It was as if the entire cliff-like stern of the boat was opening like a giant mailbox, the door hinging down to make a steel beach in the water.

Also like a mailbox, it revealed a massive cavern inside. Fifteen meters wide, nearly as tall, and a football field deep; it penetrated into the ship at sea level. Landing craft could be driven right inside the ship’s belly, loaded with vehicles from the internal garages or Marines from the barracks, and then floated back out.

The last of the fast equatorial sunset was fading from the sky as the riverine whipped around the stern at full-speed in a turn she was half sure would toss her overboard into the darkness, and roared up to the steel beach.

Inside the cavern of the Well Deck, dim red lights suggested shapes and activities she couldn’t quite make out.

# # #

The sunset was still flooding the Well Deck through the gap above the Peleliu’s unopened stern ramp as U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer Sly Stowell did his best to look calm. After nineteen years in, it was his job to radiate steadiness to his customers, the troops he was transporting. That wasn’t a problem.

He was also supposed to actually be calm during mission preparations, but it never seemed to work that way. A thousand hours of drill still never prepared him for the adrenaline rush of a live op and tonight he’d been given the “go for operation.” This section of the attack—presently loading up on his LCAC hovercraft deep inside the belly of the USS Peleliu—was all his.

“Get a Navy move-on, boys,” he shouted to the Ranger platoon loading up, “’nuff of this lazy-ass Army lollygag.”

A couple of the newbies flinched, but all the old hands just grinned at him and kept pluggin’ along. They all wore camo gear and armored vests. Their packs were only large for this mission, not massive. It was supposed to be an in and out, but it was always better to be prepared.

Two of the old hands wore Santa hats, had their Kevlar brain buckets with the clipped on night-vision gear dangling off their rifles. It was December first and he liked the spirit of it, celebrating the season, though he managed not to smile at them. It was the sworn duty of every soldier to look down on every other, especially for the Navy to look down on everyone else. It was only what

the ground pounders and sky jockeys deserved, after all.

The Peleliu was a Navy ship, even if she’d switched over from carrying Marines to now having a load of Army aboard. The transition had worried him at first. Two decades of Marines and their ways had been uprooted six months ago and now a mere platoon of U.S. Army 75th Rangers had taken their place. The swagger was much the same though.

But Peleliu had also taken on a company from the Army’s Special Operations Aviation Regiment—their secret helicopter corps. They didn’t swagger, they flew. And, as much as Sly might feel disloyal to his branch of the Service, they tended to bring much more interesting operations than the Marines.

He could hear the low roar as the engines on the Ranger vehicles selected for this mission were started up in the Peleliu’s garage decks. The three vehicles rolled down the ramp toward Sly’s hovercraft moments later.

Normally it would have taken an hour of shuffling vehicles to extricate the ones they wanted from their tight parking spaces. But fifty Rangers needed far fewer vehicles than seventeen hundred Marines. The whole ship now had an excess of space. Having a tenth of the military personnel aboard had meant that two-thirds of the Navy personnel had also moved on to other billets.

Sly had been thrilled when his application to stay had been granted. It might not be the best career move, but the Peleliu was his and he wanted to ride her until the day she died.

It had also turned out to be a far more interesting choice, though he hadn’t known it at the time. Marines were all about invade that country, or provide disaster relief for that flood or earthquake. The 160th SOAR and the U.S. Rangers were about fast and quiet ops that only rarely were released to the news.

He watched as his crew began guiding the M-ATVs onto his hovercraft. They looked like Humvees on steroids. They were taller, had v-shaped hulls for resistance against road mines, and looked far meaner.

He’d been assigned to the LCAC hovercraft since his first day aboard. First as mechanic, then loadmaster, navigator, and finally pilot. And he’d never gotten over how much she looked like a hundred-ton shoebox without the lid.

He kept an eye on Nika and Jerome as they guided the first M-ATV down the internal ramp of the Peleliu and up the front-gate ramp of the LCAC. He trusted them completely, but he was the craftmaster and it was ultimately his job to make sure it was right.

The “shoebox” presently had her two narrow ends folded down. The tall sides were made up of the four Vericor engines, fans, blowers, defensive armor, and the control and gunnery positions. The front end was folded down revealing the three-lane wide parking area of the LCAC’s deck. Between the two massive rear fans to the stern—which still reminded him of the fanboats from his family’s one trip down to the Florida Everglades where they had not seen an alligator—a one-lane wide rear ramp was folded down toward the stern.

The LCAC was the size of a basketball court, though her sides towered twice as high as the basket. She filled the wood-planked Well Deck from side to side and could carry an Abrams M1A1 Main Battle Tank from here right up onto the beach. Those days were gone, though. Now it was the noise of Army Rangers and their M-ATVs filling the cavernous space in which even a sneeze echoed painfully.

Still, the old girl could handle them and it had instilled a new life in the ship. She’d been Sly’s home for the entire two decades of his Naval career and he didn’t look forward to giving her up. He sometimes felt as if they both were hanging on out of sheer stubbornness. Hell of a thought for a guy still in his thirties. Hanging on by his fingernails? Sad.

He’d considered getting a life. Mustering out, having a pension in place and starting a new career. But he loved this one.

And he’d been aboard the eight-hundred foot ship long enough that she was now called a two-hundred and fifty meter ship instead. This was his home.

Eighteen year-old Seaman Stowell had nearly shit his uniform the day he’d reported aboard. She’d been patrolling off Mogadishu, Somalia then. In the two decades since, they’d circled the globe in both directions, though since the arrival of SOAR most of their operations had been around Africa. In nineteen years he’d traded East Africa for West Africa…and a lifetime between.

As he did before every mission, he willed this mission to please go better than the disastrous Operation Gothic Serpent—the failure immortalized by the movie Black Hawk Down that had unfolded ashore within days of his arrival aboard.

Sly didn’t feel all that different, except he no longer wanted to shit his pants before battle. He still had to consciously calm down though.

Instead of a humdrum routine settling in after the Marines Expeditionary Unit’s departure, the Rangers and SOAR had amped it back up.

SOAR was a kick-ass team, even by Navy standards. That they also had the number one Delta Force operator on the planet permanently embedded with them only meant that Sly’s life was never dull.

That was one of the reasons that Sly was looking forward to this operation. When Colonel Michael Gibson was involved, you knew it was going to be a hell-raiser.

They had the first M-ATV in place and locked down. The second one rolled up the ramp. Lieutenant Barstowe, the Rangers’ commander, came up beside him with his Santa hat still in place.

“Chief.”

“Lieutenant.”

“That’s one battle-rigged and two ambulance M-ATVs. Why don’t I like that ratio?”

“Because you’re a smart man, Chief Stowell.” The lieutenant moved up the ramp to talk with the driver of the third vehicle still waiting its turn.

They were definitely going into it heavy. That’s what finally calmed Sly’s nerves. It was the preparation he hated, once on the move he no longer had spare time to worry that he’d forgotten something.

At least he wasn’t the only one sweating it. Today was pretty typical December off the West African coast, ninety degrees and ninety percent humidity. Even the seawater from the Gulf of Guinea was limp with tepid heat as it sloshed against the outside of the hull with a flat slap and echo inside that resounded inside the Well Deck.

The last of the vehicles rolled up onto the LCAC hovercraft. For the Landing Craft, Air Cushion hovercraft—technically pronounced L.C.A.C. but more commonly El-Cack! like you were about to throw up—forty tons of vehicles and fifty Rangers was about a half load. But still he was going to keep an eagle eye on them. These young bucks might think they were the bad-asses, but until they’d faced down a Naval Chief Petty Officer—well, that was never going to happen as long as he was in the Navy.

Nika and Jerome guided the last of the vehicles into position at the center of gravity. Nika had been on his boat for two tours now and she’d better re-up next month because he had no idea who he’d ever find to replace her. She worked quickly on chaining down the third vehicle and then gave him a thumbs up. Jerome had six months as his mechanic, but had the routine down and echoed Nika’s signal. His engineer and his navigator reported ready.

The crew had already preflighted the craft, but he liked to do a final walk-around himself. There was only a foot between either side of the LCAC and the Well Deck walls.

The wooden decking along the bottom of the Well Deck was just clear of the wash of the ocean waves, so he didn’t need waders to do the inspection. For conventional landing craft that needed water to move around in, they could ballast down the stern, which lowered the ship to flood the Well Deck a meter deep or more. However, his hovercraft didn’t need such concessions. It was better this way. They could lift off dry without shedding a world of salt spray in all directions.

“Nika,” he called as he headed down to start his inspection, “get that stern gate open.” During the loading, the last of the sunset had disappeared, near darkness filled in the gap above the big door.

The Well Deck’s lights flickered as they were switched over from white to red for nighttime operations. They hadn’t flickered when he first came aboard, but she was feeling her age. He patted the inside of the Peleliu’s hull in sympathy a

s he reached the wooden planking that supported his LCAC. The huge rear gate let out a groan and began tipping out and down toward the sea.

His hovercraft was ninety feet long and fifty wide and there actually wasn’t much to see during his inspection, which was a good thing. The deflated skirts that would trap the air from the four gas turbine engines, delivering over twenty-thousand horsepower of lift and driving force, now hung in limp folds of thick black rubber. Patches covering tears and bullet holes from prior missions dotted the rippling surface. Above the rubber skirt, the aluminum sides were battered from the hard use—partly bad-guy assholes with rifles and partly harsh weather operations.

Sly saw the former as badges of courage for the old craft…and did his best not to recall how the latter was earned when nasty cross seas had slammed his craft into the sides of the Well Deck entrance. He was a damn good pilot, but there were limits to what a man could do when the ship went one way, the seas another, and his hovercraft a third.

He was halfway around his craft when he first heard it, the high whine of an incoming boat. It hadn’t been there a moment before. The Well Deck acted like a giant acoustical horn, gathering all sounds from dead astern and amplifying and focusing them like a gunshot at anyone inside the cavernous Well Deck at the time. Often you’d hear a boat before you saw it, especially at night.

He stood at the foot of the rear ramp of the hovercraft and turned, but there were no lights to see.

Then there were, incredibly close aboard. A small unit riverine craft by the arrangement of the blinding white lights that had him raising an arm to save his eyes.

The riverine was carving a high speed turn as if they intended to run right up the stern gate and into the Well Deck.

They cut their speed at the last moment with a hard reverse of the engines, but he knew it was too late for him.

The bow wave rushed up the Well Deck planking ahead of the riverine, driven bigger and faster by the abrupt nose-down of the decelerating craft. The wave came high enough to soak him to mid-calf and made him sit down abruptly. The wave washed part way up the rear ramp of his hovercraft before receding—totally soaking his butt.

White Top

White Top Thunderbolt

Thunderbolt Storm's Gift

Storm's Gift The Complete Delta Force Shooters

The Complete Delta Force Shooters At the Quietest Word (Shadowforce: Psi Book 2)

At the Quietest Word (Shadowforce: Psi Book 2) At the Slightest Sound

At the Slightest Sound Dilya's Christmas Challenge

Dilya's Christmas Challenge Raider

Raider Havoc

Havoc Carrying the Heart's Load

Carrying the Heart's Load Flying Beyond the Bar

Flying Beyond the Bar Firelights of Christmas

Firelights of Christmas Where Dreams Are Well Done

Where Dreams Are Well Done Nathan's Big Sky

Nathan's Big Sky Heart of a Russian Bear Dog

Heart of a Russian Bear Dog Drone: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 1)

Drone: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 1) Flower of Destiny

Flower of Destiny Drone

Drone Ghostrider: an NTSB-military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 4)

Ghostrider: an NTSB-military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 4) Wild Fire

Wild Fire Team Black Sheep

Team Black Sheep The Complete Delta Force Warriors

The Complete Delta Force Warriors At the Quietest Word

At the Quietest Word At the Merest Glance

At the Merest Glance Havoc: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 7)

Havoc: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 7) White Top: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 8)

White Top: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 8) Between Shadow and Soul

Between Shadow and Soul Island Christmas

Island Christmas Survive Until the Final Scene

Survive Until the Final Scene Midnight Trust

Midnight Trust Return to Eagle Cove

Return to Eagle Cove Where Dreams Reside

Where Dreams Reside Honor Flight

Honor Flight Where Dreams Are Sewn

Where Dreams Are Sewn The Complete Hotshots

The Complete Hotshots Condor

Condor I Own the Dawn

I Own the Dawn Chinook

Chinook At the Merest Glance: a military paranormal romance (Shadowforce: Psi Book 3)

At the Merest Glance: a military paranormal romance (Shadowforce: Psi Book 3) Since the First Day

Since the First Day Thunderbolt: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 2)

Thunderbolt: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 2) For Her Dark Eyes Only

For Her Dark Eyes Only Play the Right Cards

Play the Right Cards Lost Love Found in Eagle Cove

Lost Love Found in Eagle Cove Big Sky Ever After: a Montana Romance Duet

Big Sky Ever After: a Montana Romance Duet Keepsake for Eagle Cove

Keepsake for Eagle Cove At the Clearest Sensation

At the Clearest Sensation The Ides of Matt 2015

The Ides of Matt 2015 When They Just Know

When They Just Know Cave Rescue Courtship

Cave Rescue Courtship Wildfire at Dawn

Wildfire at Dawn Dawn Flight

Dawn Flight Blaze Atop Swallow Hill Lookout

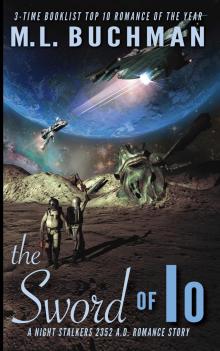

Blaze Atop Swallow Hill Lookout The Sword of Io

The Sword of Io Christmas at Steel Beach

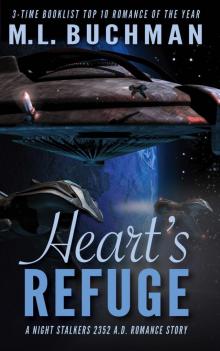

Christmas at Steel Beach Heart's Refuge

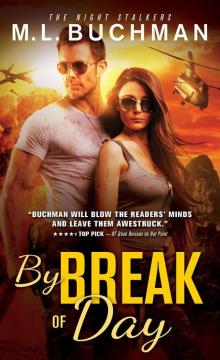

Heart's Refuge By Break of Day (The Night Stalkers)

By Break of Day (The Night Stalkers) Kee's Wedding

Kee's Wedding Just Shy of a Dream

Just Shy of a Dream Path of Love

Path of Love Ghost of Willow's Past

Ghost of Willow's Past Flash of Fire

Flash of Fire Target of the Heart

Target of the Heart Sound of Her Warrior Heart

Sound of Her Warrior Heart Target of Mine: The Night Stalkers 5E (Titan World Book 2)

Target of Mine: The Night Stalkers 5E (Titan World Book 2) The Complete Where Dreams

The Complete Where Dreams Target of One's Own

Target of One's Own For All Their Days

For All Their Days Pure Heat

Pure Heat Love's Second Chance

Love's Second Chance Target Engaged

Target Engaged Bring On the Dusk

Bring On the Dusk Wait Until Dark (The Night Stalkers)

Wait Until Dark (The Night Stalkers) Big Sky, Loyal Heart

Big Sky, Loyal Heart Welcome at Henderson's Ranch

Welcome at Henderson's Ranch Damien's Christmas

Damien's Christmas Flight to Fight

Flight to Fight Nara

Nara Looking for the Fire

Looking for the Fire Love Behind the Lines

Love Behind the Lines Peter's Christmas

Peter's Christmas In the Weeds

In the Weeds Christmas at Henderson's Ranch

Christmas at Henderson's Ranch They'd Most Certainly Be Flying

They'd Most Certainly Be Flying Fire at Gray Wolf Lookout (Firehawks Book 8)

Fire at Gray Wolf Lookout (Firehawks Book 8) Wildfire on the Skagit (Firehawks Book 9)

Wildfire on the Skagit (Firehawks Book 9) A Hotshot Christmas

A Hotshot Christmas Off the Leash

Off the Leash Where Dreams Books 1-3

Where Dreams Books 1-3 Guardian of the Heart

Guardian of the Heart The Ides of Matt 2017

The Ides of Matt 2017 Where Dreams Unfold

Where Dreams Unfold Twice the Heat

Twice the Heat Wild Justice (Delta Force Book 3)

Wild Justice (Delta Force Book 3) Flying Over the Waves

Flying Over the Waves Love in the Drop Zone

Love in the Drop Zone I Own the Dawn: The Night Stalkers

I Own the Dawn: The Night Stalkers What the Heart Holds Safe (Delta Force Book 4)

What the Heart Holds Safe (Delta Force Book 4) The Christmas Lights Objective

The Christmas Lights Objective Road to the Fire's Heart

Road to the Fire's Heart Night Rescue

Night Rescue Delta Mission: Operation Rudolph

Delta Mission: Operation Rudolph Full Blaze

Full Blaze Night Is Mine

Night Is Mine Lightning Strike to the Heart

Lightning Strike to the Heart Beale's Hawk Down

Beale's Hawk Down Circle 'Round

Circle 'Round Cookbook from Hell Reheated

Cookbook from Hell Reheated Zachary's Christmas

Zachary's Christmas Reaching Out at Henderson's Ranch

Reaching Out at Henderson's Ranch Fire Light Fire Bright

Fire Light Fire Bright The Ides of Matt 2016

The Ides of Matt 2016 Her Heart and the Friend Command

Her Heart and the Friend Command On Your Mark

On Your Mark Swap Out!

Swap Out! Heart of the Cotswolds: England

Heart of the Cotswolds: England The Phoenix Agency_The Sum Is Greater

The Phoenix Agency_The Sum Is Greater Wildfire at Larch Creek

Wildfire at Larch Creek Target Lock On Love

Target Lock On Love Second Chance Rescue

Second Chance Rescue Where Dreams Are Written

Where Dreams Are Written First Day, Every Day

First Day, Every Day Christmas at Peleliu Cove

Christmas at Peleliu Cove Heart Strike

Heart Strike Man the Guns, My Mate

Man the Guns, My Mate Emily's Wedding

Emily's Wedding Daniel's Christmas

Daniel's Christmas Frank's Independence Day

Frank's Independence Day The Phoenix Agency: The Sum Is Greater (Kindle Worlds Novella)

The Phoenix Agency: The Sum Is Greater (Kindle Worlds Novella) Roy's Independence Day

Roy's Independence Day