- Home

- M. L. Buchman

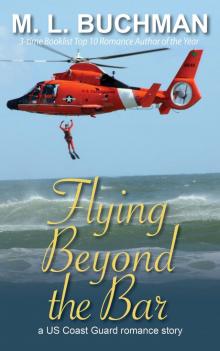

Flying Beyond the Bar

Flying Beyond the Bar Read online

Flying Beyond the Bar

US Coast Guard romance story

M. L. Buchman

Sign up for M. L. Buchman’s newsletter today

and receive:

Release News

Free Short Stories

a Free book

* * *

Get your free book today. Do it now.

free-book.mlbuchman.com

Chapter 1

The beat of the Dolphin’s rotors pounded into his body and Harvey Whitman did his best to tamp down the automatic adrenaline charge. The orange US Coast Guard HH-65C “Dolphin” search-and-rescue helicopter was hustling due west out of Astoria, Oregon and straight into the darkness of a Pacific Ocean nighttime gale. Blowing forty knots was so normal out here for a chill February night that the pilots hadn’t even remarked on it as they’d loaded up. Something about the wild smell, the taste of the salt spray that a good storm kicked up into the air, always charged him up.

“Sea state is very rough,” Vivian called out from her position as crew chief close behind the pilots but facing backwards into the cargo bay. A single strand of her dark curly hair had escaped the neatly formed bun to show between the lower edge of her flight helmet and the upper edge of the international orange survival suit they all wore. He’d always liked that curl. Even back before he knew Vivian Schroder’s name, it had captured his attention. Not that the rest of her didn’t, but there was something special about that renegade lock on the otherwise perfectly squared-away petty officer.

“Like that’s news,” Harvey didn’t need to be able to see the nighttime ocean to know that. A Douglas Sea Scale State of 6, or “very rough” meant six-meter waves. Two-story high, wind-shredded surf rated as a typical dose of ugly for this stretch of the Pacific. “Just another day at the beach.”

Vivian laughed over the intercom. Something she’d done every time he spoke his dad’s ritual phrase.

“Just another day at the beach,” Harvey recollected. Sure, Dad. Except you were a Navy clerk for two years in San Diego and never spent a day on the water no matter how many tales you’d spun for all those years—before I figured out how to look up your service record. Actually, confronting his father hadn’t changed a thing: Dad’s stories or his complete lack of interest in his son.

“Ten minutes,” one of the pilots called back.

As the helo jounced through the storm, Harvey was glad to be doing the prescribed routine tasks. Thinking about his dad was never a good sign. He started prepping in case he had to go into the water. He double-checked the ankle, wrist, and neck seals on his wet suit. He’d already pulled the long beaver-tail of his jacket between his legs and attached it to the front of his jacket. Tapping the closures of his harness assured him that everything was in place. A habit-trained series of slaps located: radio, flashlight, knife, hammer for shattering glass with a hook for cutting straps, diver’s knife, and magnesium flare. All in place.

He could see Vivian’s eyes following the same pattern as she visually confirmed everything he touched.

“Anything new?” He knew that they would have told him if there was. That he would have heard the call coming in over the intercom. It didn’t stop his need to know what he was getting into. Despite the drama in the movies, rescue swimmers didn’t enter the water all that often and he wondered if tonight would be one of the exceptions.

“Nothing new,” Vivian offered a lopsided smile at his need to know. Her smirk was almost as much of a tease as the stray curl of hair. “Fishing charter Albatross. It’s a Bayliner 35.”

He groaned to fill the pause she’d left for him to do just that. They all knew that Bayliners were designed to look good sitting at the dock. Smooth-water boats, they were never meant to go for deep-water halibut fifty miles offshore in February. Most of the Coast Guard’s rescues were in the turbulent waters of the Columbia River Bar or hunting for people dragged out to sea by the coast’s vicious rip tides. Where the river hit the Pacific was rated as the most dangerous shipping waters in the world and called for frequent assists within easy reach of the Guard’s forty-seven-foot motor lifeboats. Not tonight.

“Six aboard.” Which would load up the Dolphin to its capacity: the four crew aboard now plus the six rescued from the Bayliner. It was going to get tight in here fast. And that was assuming everything went well.

Of course they might not need rescuing at all. Most of the time it was a matter of telling them they were fine. If the situation was bad, their Dolphin’s flight would pinpoint the endangered boaters so that a motor lifeboat or cutter could come out and give them a can of fuel or a tow. Only if it was dire would the USCG send a rescue swimmer into the water to help airlift them out.

A Bayliner 35 in two-story waves—they were probably just all too seasick to stand up.

Chapter 2

“They were probably blind drunk.” Vivian recalled Harvey’s declaration about her parents at their first meal together two months ago.

“They probably came here first,” she responded, because it was about the most unlikely circumstance on the planet. Her parents in an Astoria, Oregon bar was never going to happen. Especially not one like this.

Besides, it was Christmas Eve, always a big affair at the Adler mansion. Instead of surviving Mother’s endless matchmaking, it was her third day in Oregon and Vivian had nowhere else to go. It was calm and unusually cold for the Oregon Coast—just below freezing, her breath had clouded on the night air as the whole team hustled out to Workers Tavern. It lay on a dirty back street under the Astoria-Megler Bridge that spanned the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington on the Oregon side.

The place was a total dive, and the owners were proud of that. Just in case there was any doubt, “Dive Bar” was prominently displayed in the front window below the glowing red-and-green “Breakfast All Day” sign and the blue Pabst neon. Inside was deeply marine: dark wood walls that might have been ripped off sunken ships, life rings, oars, funky art, a mounted five-foot-long fish that she didn’t recognize but definitely declared “we grow them big here”, more craft beer logos than you could count—though none so prominent as the big circular Buoy Beer Co. sign.

Most of one wall was covered in small currency bills from all over the world stapled to the wood. One of the pilots had inspected them carefully and declared that a third of them no longer even existed. The Australian pound, the Taiwanese yen, Israeli lira—he listed off a bunch of them. “And that’s before you get into the nineteen countries now using the euro.”

“The place has been a port dive bar since 1926. Get a lot of drunken sailors from a world of ports in that time.” Harvey had explained for her benefit.

Vivian wished she could get drunk. But both of their crews were on call so they all had tea or coffee with their prime rib—apparently a Workers Tavern specialty. The air was thick with the smell of grilled burgers and fries from the tiny corner kitchen tucked behind the massive U-shaped bar. She, Harvey, and the six other Coasties of their two helicopter crews had taken over one of the battered tables close by the front windows.

The lead and backup crew didn’t have to sit out at Air Station Astoria, but they had to be available for immediate deployment—which meant, “Don’t leave town and you’d better be stone cold sober.” Quite how that had turned into Christmas Eve dinner in a dive bar was something that still eluded her.

Sylvester and Hammond, her assigned pilots, had sworn this was the greatest place in all of Astoria. Having only just made it into town from the Aviation Training Center, she had nothing to judge by. The ATC, located in Mobile, Alabama, had also been far warmer. She’d wanted out of Alabama before another summer hit and had filed her request five days ago, knowing it could take months to fill. USCG thinking

had figured that meant she should be posted to Oregon within the week in the dead of winter.

Astoria, Oregon? It was the sort of place that her parents had to look up on a map before properly showing their disdain, “Really, dear?” It had been their favorite phrase for dealing with their difficult daughter. Ambition was frowned upon for old Southern families. Especially the kind of ambition that had led her into the high school auto shop instead of the glee club or the cheerleading squad.

Then, to add insult to injury, instead of going to Clemson (where her sister had married a very eligible heir to a shipping empire) or the University of South Carolina (where her brother the lawyer had just proposed to a very popular US senator’s daughter, practically guaranteeing his political career)—or even, God forbid, the University of Virginia (where she’d be at risk of meeting a Yankee stockbroker, but it couldn’t be helped)—she’d gone straight to the Aviation Institution of Maintenance in that heathen hellhole of Las Vegas. It hadn’t taken a genius to crack their code. Her parents had clearly looked up Southern schools with the highest “Meet Your Spouse Here” rankings.

Her parents had also tried to fire Captain Heath for “corrupting their daughter” with flying lessons in the family helicopter. She’d threatened to call the media rags with photos of both of her parents’ flagrant affairs—not that she actually had photos, because…ick! But the threat had been sufficient to save Captain Heath’s job and even up his salary.

The three years getting her Aviation Maintenance Technician Helicopter and two more working maintenance for Grand Canyon Helicopters had stood her in good stead when enlisting in the USCG. (“Maybe she’ll at least marry an officer.”) She’d decided to follow in Captain Heath’s footsteps…but hadn’t counted on that path leading to a dive bar on the Oregon Coast for Christmas Eve.

She’d been trying to explain her family to Harvey, for reasons that thoroughly eluded her. She typically did her best to pretend she was an orphan.

“They were probably blind drunk,” was as good an explanation as any to explain her parents. She appreciated Harvey’s levity, if not the probable accuracy of the statement. As if that would forgive any of the ways they’d tried to manipulate her.

Cocktails on the verandah at five. Mother would pour. Another one or two before dinner if there were guests, and there were always guests at the Adler’s. Whether at the Mt. Pleasant house overlooking the first tee at the Snee Farm Country Club near Charleston, or at the country house out on Lake Marion two hours inland (half an hour by helo), they entertained lavishly—which included wine and after-dinner brandies. Father would pontificate. They were relatively new, banker money, so they put on far more airs than any genuine old-money plantation owner with ten times the holdings. Six generations back they had a Yankee, post-Civil War-profiteer ancestor that they kept far more hidden than their affairs. Father’s family had “come into” large tracts of land surrounding Charleston, gambling on the city’s recovery and expansion—a bet that had paid off very handsomely.

“They offered to buy a new building for my flight school, only if the president agreed to flunk me out first,” was what she’d said that prompted his response about their state of inebriation.

Harvey’s easy laugh fit right in at the dive’s bar where a group of graybeards at the bar were trying to put together an unharmonious cacophony that would have definitely offended Wenceslas—whether or not he was a good king. They wore matching ball caps with pictures of beer steins on the front and the words “Christmas Cheers” in red-and-green glitter. They’d definitely had their share of Christmas beers.

She tried to read what lay behind Harvey’s reaction. She didn’t like revealing that she came from money—if her parents had bought the school a building, it would be far from their biggest investment that year. Revealing that wasn’t her first choice. Or her hundredth.

Then why did you say it, girl? And to the overconfident Coastie she’d known less than forty-eight hours.

To shock the unflappable rescue swimmer? As if she actually was more than she appeared because of her family’s wealth? That was her parents’ game, not hers. And if that was her goal, it hadn’t worked at all. Instead Harvey looked around the bar and nodded to himself before cutting back into his prime rib—which she had had to admit was amazingly good.

“Pop would have liked this place,” Harvey gave her a subject change. “I spent a lot of time as a kid in a place like this.”

“You grew up in a dive bar?”

“Kinda. My pop sure grew old in one,” his frown said she wasn’t the only one with parents best left in the past. “But it literally was a dive bar down in Coronado, California. I made friends with the old, Vietnam-era Navy swimmer who owned the place. Joel trained me himself off the same beaches the Navy SEALs train from.”

“And you aren’t a SEAL because…” The graybeards hunched at the bar were onto something that might have been “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” to the tune of “Jingle Bells.” Or maybe it was “Yellow Submarine.” Hard to tell.

He tipped his head as if cracking his neck. As if he was deciding whether or not to tell the truth.

She sipped her decaf coffee and waited to see where the coin was going to drop. Ten bucks would get her a hundred that he’d backpedal and cover the momentary lapse of honesty with another subject change.

Then he sighed and looked her straight in the eyes. “I decided, since I couldn’t save Pop’s life—even from his own, self-dug hole—that I’d rather save lives than take them.”

Chapter 3

“Three minutes to last known pos-i-tion,” Hammond announced over the Dolphin’s intercom from his left-hand command seat. There was a distinct hiccup in his voice when they slammed through an air pocket. Sylvester would be handling the bulk of the flying from the right seat.

The tightness in Harvey’s neck wasn’t going away. It could be three minutes to action or two hours before they had to return for a refuel if they couldn’t find the lost Bayliner. Either way, they were in for a hard ride—the storm was still on the build and was slapping around the helo like a baby bird on its first flight.

“Permission to open doors?” Harvey called forward. It was never a good idea to surprise a pilot.

“Okay to open doors,” Hammond acknowledged.

Harvey snapped a monkey line from his vest to a D-ring by the door and gave each end a good tug to make sure he didn’t get thrown out the open cargo bay door by some nasty turbulence. Only after that did he unbuckle from the small jump seat at the rear of the cargo bay. Vivian remained belted into her seat, which could slide side-to-side so that she could work from close beside either door of the cargo bay.

What mattered now was eyes on the water. More than half the challenge of a rescue was finding the boat in the first place. The fact that there’d been no updates could mean that the Bayliner’s passengers had simply forgotten to keep transmitting updates, that their radio’s battery had shorted out, or that all that was left to be found was a couple of bodies kept afloat by their life preservers.

Vivian slid her seat all the way to the port side to watch out the massive window of the emergency exit door.

Harvey moved forward enough to unlatch the heavy starboard door. It edged out three inches, then slid backwards to slam into the end of its track. Before leaning out to look, he gave it a tug to make sure it had latched open and wasn’t going to come sliding forward like a renegade guillotine when they hit the next air pocket.

“Gotta whole lot of nothing out this side.” The pilots had the landing light shining forward, hoping to spot debris or even a smoothing of the wave surface from leaked diesel fuel. But looking off to the side, there were black clouds so thick that not even moonshine could make them glow. A hundred feet below them was the hungry maw of the Pacific waters that had eaten more than two thousand ships since Robert Gray first crossed the Bar in 1792, though Native traditions spoke of washed-up Asian and European ships all the way back to 1700.

“Oh, it’

s all bright and so purty out this side,” Vivian announced breathlessly, actually getting him to turn and look. “Astoria looks like fairy lights at this time of night.” Which was fifty miles behind them—five hundred feet would be a good visibility in this mess.

The woman had made him a sucker for a straight line. Just to rub it in, she wasn’t even looking out the window as she said it, instead watching him turn and fall for her line. Yeah, she had him, hook, line, and sinker in more ways than one. He turned back to his own window to hide the smile that would have said just how much he was loving it.

Lives on the line somewhere below them, and still Vivian kept a cheerful and positive attitude. Harvey wasn’t nearly as good at that as she was, yet another thing to admire about her. In the two months since she’d arrived in Astoria and they’d started flying together, it never varied. Nobody could be that consistently upbeat—yet it didn’t feel like a facade.

When they’d lost that college student to stupidity on New Year’s Eve. She’d gone quiet, but not downbeat.

The kid and his buddy had gone out on the beach at Seaside, Oregon to play around on an eighty-foot log at least four feet in diameter. Didn’t they get that the ocean had put it there and could toss it around any time it wanted? There were plenty of signs posted to stay off the driftwood—but they’d ignored those. They hadn’t even started drinking yet, so they hadn’t had that as an excuse either.

The kid washed out to sea had been the lucky one, probably dead from hypothermia inside the first ten minutes. His buddy had almost bled to death before they could dig him out from where a sneaker wave had lifted the twenty-five-ton log long enough for him to fall under it before the water dropped it back down. He’d had to have both of his legs amputated. They finally found first kid’s battered body washed up on boulders far out along the South Jetty of the Columbia River, ten miles to the north of Seaside.

White Top

White Top Thunderbolt

Thunderbolt Storm's Gift

Storm's Gift The Complete Delta Force Shooters

The Complete Delta Force Shooters At the Quietest Word (Shadowforce: Psi Book 2)

At the Quietest Word (Shadowforce: Psi Book 2) At the Slightest Sound

At the Slightest Sound Dilya's Christmas Challenge

Dilya's Christmas Challenge Raider

Raider Havoc

Havoc Carrying the Heart's Load

Carrying the Heart's Load Flying Beyond the Bar

Flying Beyond the Bar Firelights of Christmas

Firelights of Christmas Where Dreams Are Well Done

Where Dreams Are Well Done Nathan's Big Sky

Nathan's Big Sky Heart of a Russian Bear Dog

Heart of a Russian Bear Dog Drone: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 1)

Drone: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 1) Flower of Destiny

Flower of Destiny Drone

Drone Ghostrider: an NTSB-military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 4)

Ghostrider: an NTSB-military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 4) Wild Fire

Wild Fire Team Black Sheep

Team Black Sheep The Complete Delta Force Warriors

The Complete Delta Force Warriors At the Quietest Word

At the Quietest Word At the Merest Glance

At the Merest Glance Havoc: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 7)

Havoc: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 7) White Top: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 8)

White Top: a political technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 8) Between Shadow and Soul

Between Shadow and Soul Island Christmas

Island Christmas Survive Until the Final Scene

Survive Until the Final Scene Midnight Trust

Midnight Trust Return to Eagle Cove

Return to Eagle Cove Where Dreams Reside

Where Dreams Reside Honor Flight

Honor Flight Where Dreams Are Sewn

Where Dreams Are Sewn The Complete Hotshots

The Complete Hotshots Condor

Condor I Own the Dawn

I Own the Dawn Chinook

Chinook At the Merest Glance: a military paranormal romance (Shadowforce: Psi Book 3)

At the Merest Glance: a military paranormal romance (Shadowforce: Psi Book 3) Since the First Day

Since the First Day Thunderbolt: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 2)

Thunderbolt: an NTSB / military technothriller (Miranda Chase Book 2) For Her Dark Eyes Only

For Her Dark Eyes Only Play the Right Cards

Play the Right Cards Lost Love Found in Eagle Cove

Lost Love Found in Eagle Cove Big Sky Ever After: a Montana Romance Duet

Big Sky Ever After: a Montana Romance Duet Keepsake for Eagle Cove

Keepsake for Eagle Cove At the Clearest Sensation

At the Clearest Sensation The Ides of Matt 2015

The Ides of Matt 2015 When They Just Know

When They Just Know Cave Rescue Courtship

Cave Rescue Courtship Wildfire at Dawn

Wildfire at Dawn Dawn Flight

Dawn Flight Blaze Atop Swallow Hill Lookout

Blaze Atop Swallow Hill Lookout The Sword of Io

The Sword of Io Christmas at Steel Beach

Christmas at Steel Beach Heart's Refuge

Heart's Refuge By Break of Day (The Night Stalkers)

By Break of Day (The Night Stalkers) Kee's Wedding

Kee's Wedding Just Shy of a Dream

Just Shy of a Dream Path of Love

Path of Love Ghost of Willow's Past

Ghost of Willow's Past Flash of Fire

Flash of Fire Target of the Heart

Target of the Heart Sound of Her Warrior Heart

Sound of Her Warrior Heart Target of Mine: The Night Stalkers 5E (Titan World Book 2)

Target of Mine: The Night Stalkers 5E (Titan World Book 2) The Complete Where Dreams

The Complete Where Dreams Target of One's Own

Target of One's Own For All Their Days

For All Their Days Pure Heat

Pure Heat Love's Second Chance

Love's Second Chance Target Engaged

Target Engaged Bring On the Dusk

Bring On the Dusk Wait Until Dark (The Night Stalkers)

Wait Until Dark (The Night Stalkers) Big Sky, Loyal Heart

Big Sky, Loyal Heart Welcome at Henderson's Ranch

Welcome at Henderson's Ranch Damien's Christmas

Damien's Christmas Flight to Fight

Flight to Fight Nara

Nara Looking for the Fire

Looking for the Fire Love Behind the Lines

Love Behind the Lines Peter's Christmas

Peter's Christmas In the Weeds

In the Weeds Christmas at Henderson's Ranch

Christmas at Henderson's Ranch They'd Most Certainly Be Flying

They'd Most Certainly Be Flying Fire at Gray Wolf Lookout (Firehawks Book 8)

Fire at Gray Wolf Lookout (Firehawks Book 8) Wildfire on the Skagit (Firehawks Book 9)

Wildfire on the Skagit (Firehawks Book 9) A Hotshot Christmas

A Hotshot Christmas Off the Leash

Off the Leash Where Dreams Books 1-3

Where Dreams Books 1-3 Guardian of the Heart

Guardian of the Heart The Ides of Matt 2017

The Ides of Matt 2017 Where Dreams Unfold

Where Dreams Unfold Twice the Heat

Twice the Heat Wild Justice (Delta Force Book 3)

Wild Justice (Delta Force Book 3) Flying Over the Waves

Flying Over the Waves Love in the Drop Zone

Love in the Drop Zone I Own the Dawn: The Night Stalkers

I Own the Dawn: The Night Stalkers What the Heart Holds Safe (Delta Force Book 4)

What the Heart Holds Safe (Delta Force Book 4) The Christmas Lights Objective

The Christmas Lights Objective Road to the Fire's Heart

Road to the Fire's Heart Night Rescue

Night Rescue Delta Mission: Operation Rudolph

Delta Mission: Operation Rudolph Full Blaze

Full Blaze Night Is Mine

Night Is Mine Lightning Strike to the Heart

Lightning Strike to the Heart Beale's Hawk Down

Beale's Hawk Down Circle 'Round

Circle 'Round Cookbook from Hell Reheated

Cookbook from Hell Reheated Zachary's Christmas

Zachary's Christmas Reaching Out at Henderson's Ranch

Reaching Out at Henderson's Ranch Fire Light Fire Bright

Fire Light Fire Bright The Ides of Matt 2016

The Ides of Matt 2016 Her Heart and the Friend Command

Her Heart and the Friend Command On Your Mark

On Your Mark Swap Out!

Swap Out! Heart of the Cotswolds: England

Heart of the Cotswolds: England The Phoenix Agency_The Sum Is Greater

The Phoenix Agency_The Sum Is Greater Wildfire at Larch Creek

Wildfire at Larch Creek Target Lock On Love

Target Lock On Love Second Chance Rescue

Second Chance Rescue Where Dreams Are Written

Where Dreams Are Written First Day, Every Day

First Day, Every Day Christmas at Peleliu Cove

Christmas at Peleliu Cove Heart Strike

Heart Strike Man the Guns, My Mate

Man the Guns, My Mate Emily's Wedding

Emily's Wedding Daniel's Christmas

Daniel's Christmas Frank's Independence Day

Frank's Independence Day The Phoenix Agency: The Sum Is Greater (Kindle Worlds Novella)

The Phoenix Agency: The Sum Is Greater (Kindle Worlds Novella) Roy's Independence Day

Roy's Independence Day